Book: Democratizing AI

Calls for ‘democratizing AI’ are everywhere, particularly during the latest generative AI deployment wave. While this wave has prompted escalating fears about AI posing an existential threat to humanity, there has also been an uptick in unbridled techno-optimism about the positive potential of a large number of people starting to integrate generative AI tools into every aspect of their daily lives. Surely, the thinking goes, this will ‘democratize AI’ by making sophisticated technology much more accessible to ordinary citizens without specialized expertise.

But it would be misguided to jump to that conclusion.

Just because generative AI is at all of our fingertips, that does not mean it is truly in our hands.

As a democratic constituency, we currently find ourselves in a choice environment marred by an asymmetrical concentration of power, wealth, and information in the hands of a small group of AI deployers, coupled with a widespread dispersion of AI-related risks across the demos at large. In this book, I argue that this asymmetry creates a particular type of democratic legitimacy deficit that warrants a particular type of collective response.

AI deployers, most of whom are oligopolistic corporate actors partial to fundamentally antidemocratic political ideologies and not subject to direct democratic authorization, are currently able to set AI regulation agendas unliterally. They do so either by increasingly intervening in governmental institutions directly, or by the mere act of simply developing new tools and then granting public access to them. At the same time, these actors offload responsibilities for dealing with AI deployment’s potential harmful consequences onto government actors and—by extension—democratic constituencies.

Once democratic constituencies relinquish the power to effectively set AI policy agendas, and find themselves locked in a dynamic of reacting to an unduly narrow and risky cluster of options presented to them by an unrepresentative subset of the democratic constituency, they forfeit an essential feature of democracy itself: the right to exercise free and equal anticipatory control over the nature and scope of decisions shaping their shared future.

Democratic constituencies need to stop uncritically accepting AI exceptionalism: the view that AI is an inherently mysterious, highly unusual policy domain that cannot possibly be subjected to democratic scrutiny.

Instead, all of us—as democratic constituencies—must identify ways of taking charge, inspired by the ways in which other complex science and technology policy domains have been democratized. This book offers an AI democratization Playbook outlining concrete strategies for taking back control—by harnessing the power of tech workers, by amplifying the democratic impact of independent expert voices in AI policy, by identifying innovative ways of mobilizing ‘regular’ citizens, and by rethinking structures of ownership in the technology sector.

… with critical commentary by

Thomas Christiano & Ritwik Agrawal, Chiara Cordelli, Regina Kreide, Mathias Risse, Allison Stanger, and Nadia Urbinati.

Papers

Don’t Give Up on Democratizing AI for the Wrong Reasons

NeurIPS (2025) Position Paper

Co-authored with Andrew Zeppa, Srijan Pandey, Kenneth Diao.

Distinguishing Two Features of Accountability for AI Technologies.

Nature Machine Intelligence 4 (2022): 734–736.

(co-authored with Zoe Porter, Phillip Morgen, John McDermid, Tom Lawton, and Ibrahim Habli)

The claim that the AI community, or society at large, should ‘democratize AI’ has attracted considerable critical attention and controversy. Two core problems have arisen and remain unsolved: conceptual disagreement persists about what democratizing AI means, and normative disagreement persists over whether democratizing AI is ethically and politically desirable.

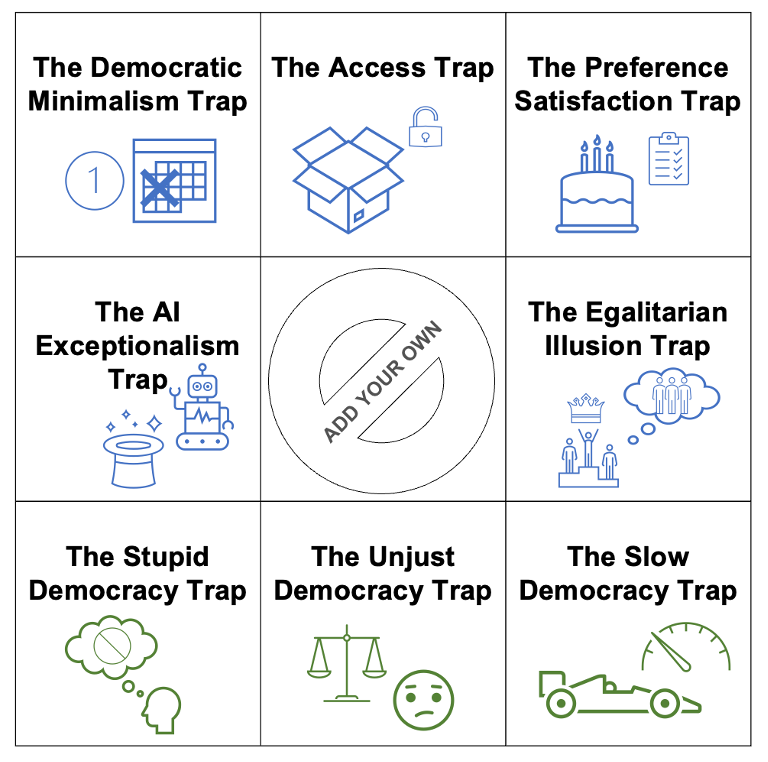

We identify eight common AI democratization traps: democratization-skeptical arguments that seem plausible at first glance, but turn out to be misconceptions. We develop arguments about how to resist each trap.

We conclude that, while AI democratization may well have drawbacks, we should be cautious about dismissing AI democratization prematurely and for the wrong reasons. We offer a constructive roadmap for developing alternative conceptual and normative approaches to democratizing AI that successfully avoid the traps.

Proceed with Caution.

Canadian Journal of Philosophy 52, no. 1 (2022): 6-25.

Co-authored with Chad Lee-Stronach.

It is becoming more common that the decision-makers in private and public institutions are predictive algorithmic systems, not humans. This article argues that relying on algorithmic systems is procedurally unjust in contexts involving background conditions of structural injustice. Under such nonideal conditions, algorithmic systems, if left to their own devices, cannot meet a necessary condition of procedural justice, because they fail to provide a sufficiently nuanced model of which cases count as relevantly similar. Resolving this problem requires deliberative capacities uniquely available to human agents. After exploring the limitations of existing formal algorithmic fairness strategies, the article argues that procedural justice requires that human agents relying wholly or in part on algorithmic systems proceed with caution: by avoiding doxastic negligence about algorithmic outputs, by exercising deliberative capacities when making similarity judgments, and by suspending belief and gathering additional information in light of higher-order uncertainty.

Introduction: The Political Philosophy of Data and AI.

Canadian Journal of Philosophy 52, no. 1 (2022): 1-5.

Co-authored with Kate Vredenburgh and Seth Lazar.

There is a thriving literature in other disciplines on the legal and political implications of big data and AI, as well as a rapidly growing literature within philosophy concerning ethical problems surrounding AI. There is relatively little work to date, however, from the perspective of political philosophy. This special issue was borne out of a recognition that political philosophy has a crucial role to play in conversations about how AI ought to reshape our joint political, social, and economic life. The widespread deployment of AI calls attention to fundamental, long-standing problems in political philosophy with renewed urgency, and creates genuinely new philosophical problems of political significance.

Criminal Disenfranchisement and the Concept of Political Wrongdoing

Philosophy & Public Affairs 47, no. 4 (2019): 378-411.

Disagreement persists about when, if at all, disenfranchisement is a fitting response to criminal wrongdoing of type X. Positive retributivists endorse a permissive view of fittingness: on this view, disenfranchising a remarkably wide range of morally serious criminal wrongdoers is justified. But defining fittingness in the context of criminal disenfranchisement in such broad terms is implausible, since many crimes sanctioned via disenfranchisement have little to do with democratic participation in the first place: the link between the nature of a criminal act X (the ‘desert basis’) and a fitting sanction Y is insufficiently direct in such cases. I define a new, much narrower account of the kind of criminal wrongdoing which is a more plausible desert basis for disenfranchisement: ‘political wrongdoing’, such as electioneering, corruption, or conspiracy with foreign powers. I conclude that widespread blanket and post-incarceration disenfranchisement policies are overinclusive, because they disenfranchise persons guilty of serious, but non-political, criminal wrongdoing. While such overinclusiveness is objectionable in any context, it is particularly objectionable in circumstances in which it has additional large-scale collateral consequences, for instance by perpetuating existing structures of racial injustice. At the same time, current policies are underinclusive, thus hindering the aim of holding political wrongdoers accountable.

Introduction: The Historical Rawls

Modern Intellectual History 18, no. 4 (2021): 899-905.

Introduction to the Forum on “The Historical Rawls,” co-authored with Sophie Smith and Teresa M. Bejan.

Economic Participation Rights and the All-Affected Principle

Global Justice: Theory Practice Rhetoric 10, no. 2 (2017): 1-21.

The democratic boundary problem raises the question of who has democratic participation rights in a given polity and why. One possible solution to this problem is the all-affected principle (AAP), according to which a polity ought to enfranchise all persons whose interests are affected by the polity’s decisions in a morally significant way. While AAP offers a plausible principle of democratic enfranchisement, its supporters have so far not paid sufficient attention to economic participation rights. I argue that if one commits oneself to AAP, one must also commit oneself to the view that political participation rights are not necessarily the only, and not necessarily the best, way to protect morally weighty interests. I also argue that economic participation rights raise important worries about democratic accountability, which is why their exercise must be constrained by a number of moral duties.

Editing

The Political Philosophy of Data and AI.

Canadian Journal of Philosophy (2022).

A special issue co-edited with Kate Vredenburgh and Seth Lazar.

The Historical Rawls.

Modern Intellectual History (2021).

A special issue co-edited with Teresa Bejan and Sophie Smith.